Capturing Legacy with Future Hackney

Interview by Esta Maffrett | 24.05.24

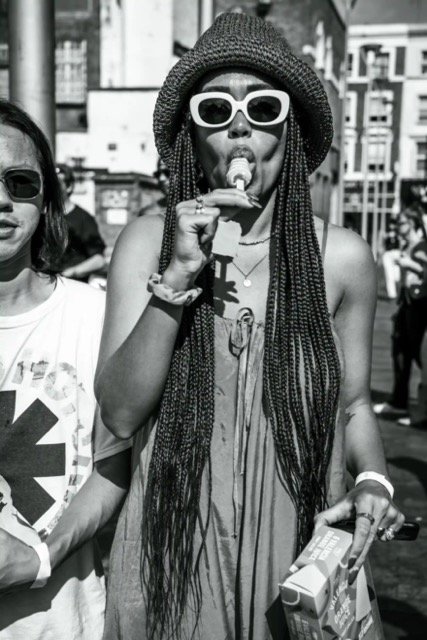

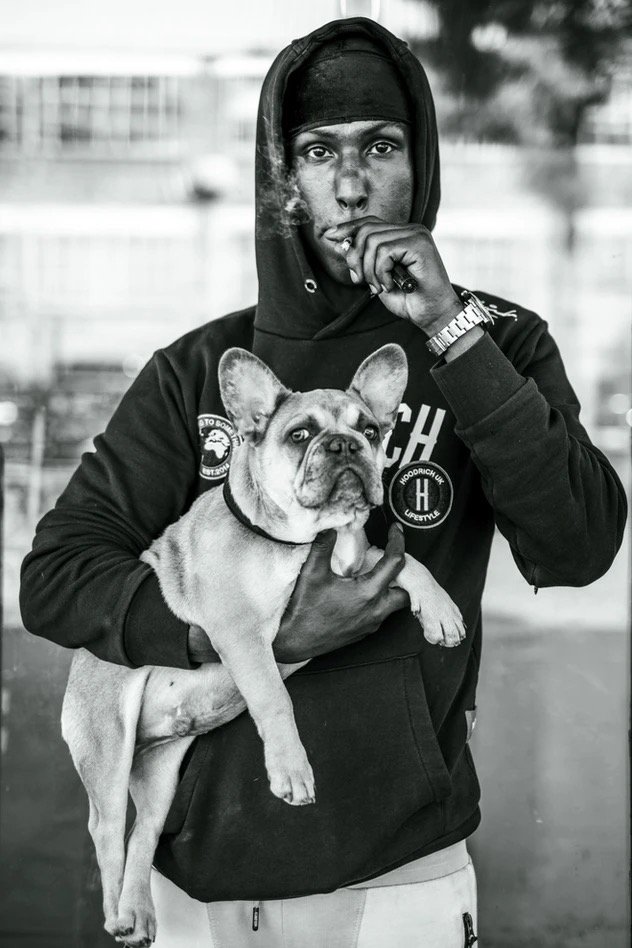

If you’re from East London or have visited in the past few years then you’ve probably become familiar with some of Future Hackney’s outdoor exhibitions. Taking over the streets are their large portraits capturing the local community and photographed by the younger generations. It’s work on the streets that gives back to the streets and they’re not stopping anytime soon.

How did Future Hackney come about and what has the journey looked like?

We started as Inner City Films in 2002 and that was mainly working across the whole of London doing small art and film projects. We worked in young offenders institutes, prisons, housing estates and with groups who were marginalised by society in some way through no fault of their own. That was really successful. We done great projects with Asian elderly centres who told us about their histories and how great it was to be able to talk about some of the emotional pain they’d been through. And also generally just working with young people and getting around London. Then we decided that really it'd be better if we concentrated on one area and we wanted to develop the photography and oral history side of the project rather than the film. So in 2018 we became known as Future Hackney and centred around East London. We do occasional projects over in South but they’re very few and far between. We also have a project with City of London.

What might a project look like at Future Hackney? Are there any processes you always include?

The main project we run is documentary and street photography in Dalston. We get funded by National Lottery Heritage Fund and a range of other funders including Future Foundation for London, Weavers Benevolent Fund and Hackney Council. We discovered through working in Dalston over the years that there are so many rich histories that hadn’t been documented, so we’ve built an archive of around three years of images and stories.

On a typical day we either work on the streets, that’s me and my colleague Wayne Critchlow, or it will be that we’re working with a group of young people and training them. We get them to take photos with small digital cameras, we’ve got phones, we’ve got film cameras, and getting them to get to know people and their stories. In an age of media where it’s celebrities and people with money that are seen to be important it really goes against that to say ordinary people around us have the best stories, they have the best lives and the most interesting histories. There is a definite interest in us as humans to want to know about the people around us. On a typical day Wayne and I go out and get stories and photographs on the streets or we have groups of young people with us. We also work very closely with the vulnerable and older community who know our work and will help us as assistants and volunteers.

More recently we’ve widened the project from being Dalston's Radical Black History to being Dalston’s Radical History. This includes the Caribbean and African communities who really made the space unique and special up until now where you’ve got a lot of the LGBTQ community, artists and young people struggling but keeping it vibrant and open for people who are different in some way.

What is the power of photographic storytelling?

I think the power is getting people to trust you. Letting them know where the photos are going. It’s not for another coffee table book that we’ll sell for profit, that’s been done and it’s boring and it values the photographer rather than the community who have engaged.

For example, with the Dalston project which we have become known for we’re going to put up a big street gallery right opposite the iconic peace mural in the centre of Dalston. There will be ten large photographs and stories from churches to nightclubs. We’ll then have an inside gallery at the BSMT Space which is on Kingsland High Street, on the strip we’re documenting. It's a very trendy cool gallery and through Heritage Lottery we’re having an exhibition there from October 17th with our photos and Connie Swift. As well as exhibiting Connie’s photos we have another two artists Tom Hunter and Neil Martinson who have been photographing Hackney since the seventies. It will be over Black History Month and will mix Caribbean and African histories alongside more current histories of younger and newer communities there now.

And we'll have a third gallery at the factory on Sandringham Road. There'll be some images with sculptures from a sculptor called Bart.

Your projects are very grounded in physical space. What are the feelings and attitudes from the communities you work with about their ownerships of local space?

A lot of the outreach that we do works really well because young people understand where they come from, they know their territory and they feel safe there. They know older people in the community and it’s very grounding for them. This makes it easier for us to take photos and we don’t have people shouting at us to ask why we’re photographing them. A lot of that is avoided which makes a huge difference with street photography.

The work we do is very clear that we put back into the community. Our exhibitions are free for people to come to and we welcome the wider community. The outside gallery, on the streets, work for people who don’t like going into gallery spaces which we think is really important. It’s important we’re not always looking at models on our streets or adverts to buy things. It’s refreshing and innovative to put the actual community on the street

I agree, what’s the point of taking work that is so grounded out of its own context and into a book or exclusive gallery. Our own history should be written on the streets and walls we walk past everyday. Going forward do you want to look to the past more or the future? Or focus on young people in the present and capturing that today?

I think that past stories are really important. Recently we’ve documented Newton who sadly passed a couple of weeks ago aged 88. He had this fantastic story about coming here in the fifties and setting up a club because back then it was quite segregated here and there weren’t many social spaces for the black community. Newton wanted a space for all communities to mix and so he opened the Four Aces where people could appreciate good music together which would have been revolutionary at the time. So his story is grounding for our stories today. These are the people that made the city different and more open and acceptable, and brought in great music. So we really just began documenting African and Caribbean community but then we began to realise they left a legacy.

That legacy has continued and if we then avoid getting the stories of young people we’re missing out where these stories ended up. Dalston was created to be a space for marginalised people and newer communities tell you that legacy has not been lost.

88 years of a story is huge and the changes that Newton would have seen would be things we couldn’t even imagine. What I find interesting about young people's stories is that they’re different to Newton’s but the struggle is still there. There is still a reason why people feel excluded. Often those reasons come down to slight differences and feelings. There’s a link that I'm trying to form at the moment and that’s why the project is called From Churches to Nightclubs. Because we’re documenting the Pentecostal Church which has a lot of older voices but we’re also going into the nightclubs and asking young people what it is that makes that space special. It’s really interesting and I'm excited to see it.

Future Hackney will exhibit at BSMT Space on Kingsland High Street from 17th - 29th October 2024.